In a sprawling, tented camp on Syria’s northwestern border with Turkey, Omar Mubarak and his wife wait anxiously.

Since they fled bombing in their hometown of Idlib three weeks ago for Atmeh camp, the couple in their 20s have whittled down their possessions to a single piece of luggage: a black duffle bag emblazoned with a cartoon airplane.

They’ve been waiting for a text message, they told The New Humanitarian by phone.

Soon after they arrived at the camp, Mubarak contacted a local smuggler. He is demanding $700 a person to guide the grocer, his wife, and a dozen other Syrians over the nearby border into Turkey. They pay only if they make it across.

Smugglers say there’s a newly booming black market to get desperate families out of rebel-held northwest Syria, prompted by the drastic increase in violence after a fragile ceasefire broke down in late April.

Getting out can cost from hundreds of dollars to thousands of dollars per person. But few such trips, conducted under the cover of darkness, end in success.

The Syrian government and allied Russian forces are using airstrikes, rebel forces are fighting back, and an estimated 330,000 people have been forced to flee Idlib province and its surroundings since early May. Earlier this month, the UN said as many as two million people may try to flee towards the closed Turkish border if the violence intensifies, escaping a situation UN relief chief Mark Lowcock has called a “humanitarian disaster unfolding before our eyes.”

Nevertheless, Omar and his wife waited for the signal that the route is clear. Once they get the green light, they’ll board a vehicle towards the border wall, then climb a ladder to jump down some three metres to Turkish soil.

That text came on 10 June. “[Our smuggler] told us there is going to be an attempt today,” Omar wrote in a WhatsApp message. They planned to wait on the Syrian side until a guide determined that Turkish border guards were not around. Then, they’d cross.

“We’re leaving the camp tonight, at 9pm,” he wrote.

‘They’re just selling their things and going to Turkey’

The journey has taken on new urgency since the beginning of the Idlib assault; three smugglers, initially put in touch with TNH by trusted contacts in Idlib, said that more people are reaching out for their services than ever.

Nour, a smuggler who lives just two kilometres from the Turkish border in a Syrian town called Darkoush, said he now receives at least 15 requests a day, more than twice the number he got late last year. He charges $250 per person for the journey, and asked to be identified by his first name only because of the sensitivity of his work.

The increase in demand is despite the fact that most people, including Omar and his family, never make it. The family was spotted by Turkish soldiers and hastily scrambled back over the wall. Getting caught could mean detainment, or worse.

For years, this corner of northwestern Syria has been the nexus of a people-smuggling trade, despite the fact that the border has been largely closed since 2015. An estimated 3.6 million Syrian refugees are already in Turkey.

“People – a lot of them – can no longer make ends meet in Syria.”

Those hoping to cross face a 10-foot concrete wall stretching hundreds of kilometres as well as Turkish military patrols. Turkish border guards “shoot at incoming people, and in many cases they shoot to kill,” said Sara Kayyali, a researcher for Human Rights Watch, the New York-based watchdog that has documented shootings along the border as far back as 2016.

About 60 percent of Nour’s clients get into Turkey, he said by phone, without revealing whether that includes people who get across only to be forced back by Turkish soldiers.

“People – a lot of them – can no longer make ends meet in Syria,” he said. “They’re just selling their things and going to Turkey.”

Another smuggler, Mohammad al-Ali in Idlib, said the number of requests he receives has doubled in recent months. Farid, another smuggler who also asked that his last name not be published, said he gets up to 100 clients a week.

“It’s crazy. There’s a huge increase,” he said.

‘We’ve gotten used to this life’ under bombardment

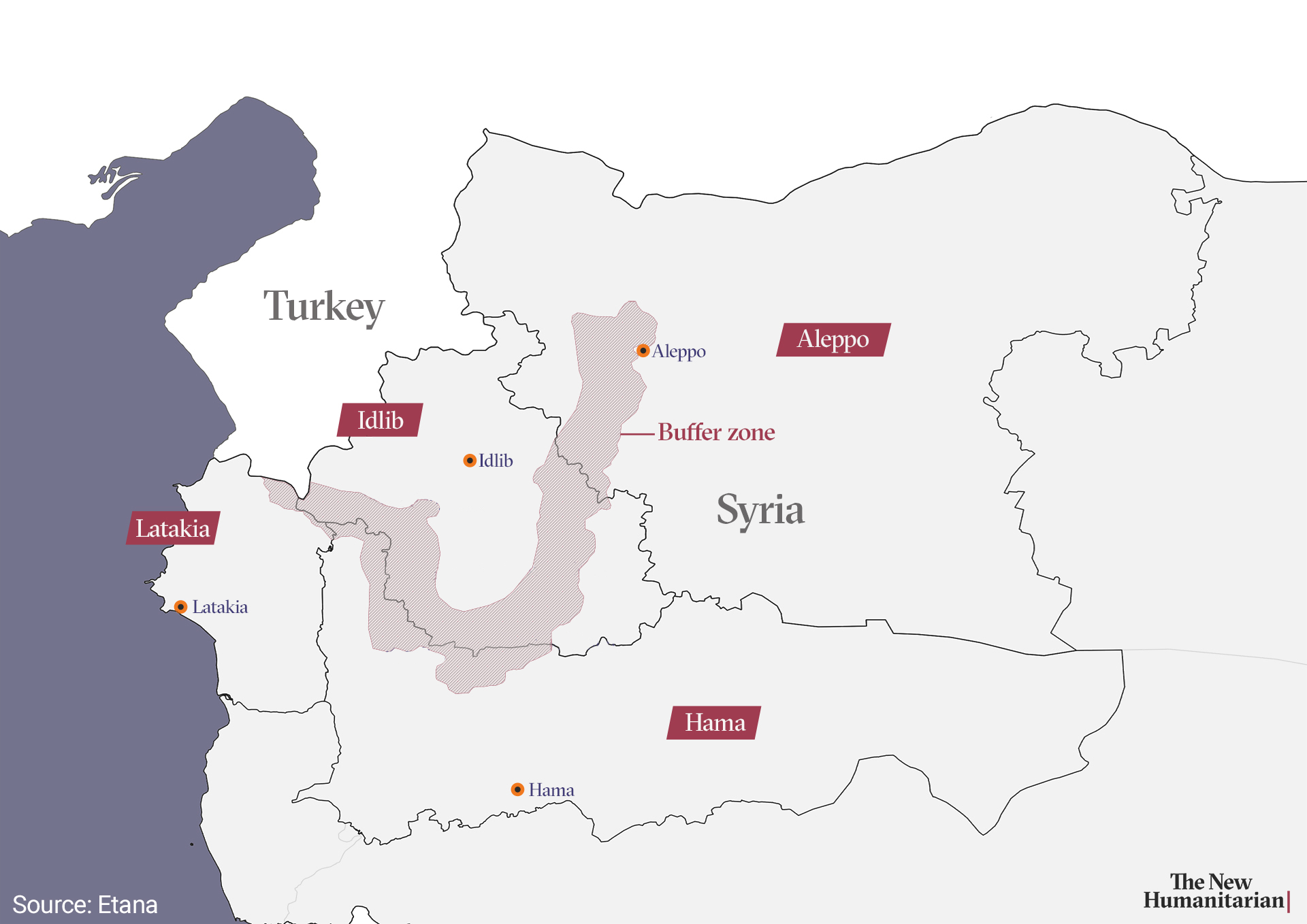

Idlib and its surroundings were relatively calm since last September, thanks to a Russia-Turkey mediated buffer zone that held off a widely anticipated government offensive in Idlib.

But that quiet is long gone. Hundreds of thousands have fled their hometowns, while others, who often lack the resources to escape, continue to live with the daily bombardment.

“We’ve gotten used to this life,” said Qusai al-Khateeb, an opposition-aligned journalist who lives in one of Idlib’s few bomb shelters with his wife and two-year-old son. “For us, this is normal,” he said, speaking by phone.

“You have individuals who’ve taken this incredibly dangerous journey 10, even 20, times and have not succeeded,” said Kayyali, the human rights researcher. She said increased Turkish checkpoints and continued use of force by border guards are preventing large numbers of Syrians from escaping the war, despite the rise in requests noted by people smugglers.

Omar Kadkoy, a policy analyst at the Ankara-based Economic Policy Research Foundation, or TEPAV, says a flagging economy prevents Turkey from opening its borders once again to more refugees. There’s also a growing push – from President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and other politicians – to encourage Syrian refugees to return home.

“Opening the doors for more Syrian refugees means opening up more accommodation, more support,” Kadkoy said.

For years, Qusai has chosen to live in danger to cover the war. But now the 24-year-old has his sights on flight.

Since May, the family has attempted to cross the wall to Turkey at least five times, usually by night and after an hours-long car ride.

They’ve never made it.

“Despite all this tragedy and danger, even this is better than staying under the bombs.”

“My son is very young,” Qusai said. “When we arrive at the border wall, he starts crying and the smugglers want me to give him sleeping medication.” Though his son’s crying would likely give away their position, he feared an accidental overdose.

“I refused,” Qusai said.

He is still waiting for another chance.

In the Atmeh camp, Omar and his wife remain determined.

They’ve already been on the Turkish side of the wall – at least 100 metres inside by Omar’s count – before spotting the lights of Turkish border guards and racing back into the war zone.

That was three weeks ago; the last time they attempted the crossing. They are waiting for their chance to try again.

“I’m living in a state of constant anxiety,” Omar said. “Despite all this tragedy and danger, even this is better than staying under the bombs.”

(TOP PHOTO: Displaced Syrian men pack their belongings to sell in the rebel-held western part of Aleppo province, 13 June 2019.)

me/mf/as/ag